‘The last invention humans will ever need to make.’

No, it’s not a surgically attachable selfie stick. In a recent interview, Prof. Stephen Hawking warningly referred to full artificial intelligence, that is, the development of robots with intelligence that equals – or surpasses – our own. Just last week, critics were calling Myon’s lead performance in the Berlin Opera House’s My Square Lady somewhat ‘mechanical’, on account of, well…that it’s a robot (pictured in action above). And lately, here in the UK, new sci-fi drama Humans made its debut on Channel 4 after causing some confusion with a clever launch campaign that involved adverts, London shop fronts and E-bay listings for ‘synthetic humans’. The show, set in a parallel present-day where humanoid household robots are as commonplace as tablets and smart-phones, seems intriguing so far and raises some interesting questions which got me thinking and inspired this post.

Our fear of the rise of the robots is hardly new, it’s been documented by films for decades. Since 1991 we’ve even been putting ourselves on trial against robots in the annual Loebner Prize Turing test, to see if we can still tell the difference. But besides this existential fear, what is it about some robots that makes them just a bit creepy?

Creepy or cute? The above are all real robots. The third is Kaspar2, used to teach social interaction to autistic children.

Creepy or cute? The above are all real robots. The third is Kaspar2, used to teach social interaction to autistic children.

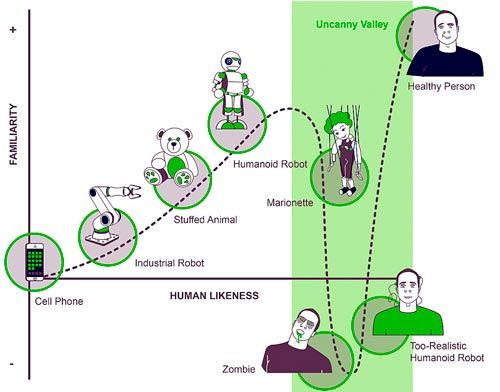

We’ve all experienced it before, that feeling when you look at a robot, or even a doll or CGI film character and there’s just something not quite right. Generally, the more human something looks, the more comfortable we are looking it. But, at a certain point of not-quite human resemblance, our positive feeling towards the robot or character suddenly drops off and we feel eerily unsettled. Welcome to the Uncanny Valley. This is the name for the point where a human-like face gives us the creeps, first described by Masashiro Moroi in a 1970 journal paper. It looks a bit like this:

It’s actually still debated as to whether this phenomenon really exists, since there hasn’t been much scientific investigation of it. But if it is real, it is likely linked with the neuroscience of the way we perceive faces.

We know that, for us humans, face perception is an incredibly important ability. This is partly from the study of people with prosopagnosia – also known as ‘face blindness’. A fold in the surface of the right brain called the fusiform gyrus, is thought to be primarily responsible for recognising faces, and damage to this leads to the strange condition where vision is normal – the person can see the face – but they can’t recognise it as a face. To get an idea of what this might be like, imagine if faces were like abstract paintings. You can see the painting in front of you perfectly clearly, but no matter how you tilt your head or squint, you just don’t ‘get’ what it’s meant to be. The fact that many prosopagnosiacs have no trouble recognising other object suggests that our brains have developed networks of neurons – areas like the fusiform gyrus – that are exclusively for face perception, and brains don’t waste energy and resources crafting specific networks if they’re not important

In fact, without our ability to pick out faces, we might not have survived long enough to even start scratching our heads about robots. And we’re very good at it, in fact perhaps a bit too good: we’ll see faces in anything. Potatoes. Outer space. But, importantly, face perception is not just identifying a face. Two dots and line on a sheet of paper is a ‘face’, but we instantly know it’s not a real one. So when we recognise a face, what we’re also looking for is the indication that it’s actually more than just a pretty face (perhaps fortunately, for some of us).

We have the expectation that a convincing enough human-like face means: ‘hey, this is a being with a mind: the ability to think, feel, decide and perform higher functions just like I can’, basically that the lights are on and, yes, somebody is at home. This is unsurprising, since we display what we’re thinking and feeling for all to see in a roughly decodable form on our intricate canvas of eye and facial muscles. And so this expectation, in the context of survival, makes sense: a creepy doll might look murderously angry, but we know that it’s not actually angry – it doesn’t have a brain – and so we don’t need to waste time and energy anticipating what it could do next.*

Expectation is a huge part of human survival and our day-to-day lives. Every morning I wake up and make myself a bowl of cereal with wild abandon, because I don’t expect my housemates to have poisoned all my food overnight. Stressing out about extremely unlikely scenarios is a waste of time and energy. So it’s unsurprising that, generally, we don’t like it when our expectations are violated. And, according to one theory, this is why faces in the uncanny valley creep us out: they violate our expectation that a human-like face indicates a being with a mind.

A 2010 study attempted to investigate 2 specific aspects that might be involved in this effect: agency (that is, whether something can move around, make things happen and do things independently) and experience (whether something is capable of things like emotion and sensation). Participants had to scroll through a spectrum of faces, which were increasingly morphed the face of a mannequin, and identify various cut-off points e.g. for pleasant vs. unpleasant and living vs. not living. The researchers concluded that when we are confronted with a machine, which we know is not capable of complex experiences such as emotion and sensation, we will be unsettled if it has an appearance that contradicts this. So essentially, things start to get creepy when it looks like the lights are on, but we know nobody is home. It seems that eyes may be an important factor in this, as we know that when we look at faces it’s the eyes we look at more than any other feature. But in short, the conclusion would appear to be that ‘we are happy to have robots that do things, but not feel things.’

So, while we don’t yet know enough about how a brain works to be able to engineer one in a robot that approaches anything as close as our complexity, we can at least go some way to making them look less creepy.

The robots have not risen against us yet, but in the meantime artificial intelligence is giving us plenty of important questions to think about, not least: ‘how far down the uncanny valley am I?’

*Unless, of course, you should ever find yourself in a horror film, in which case: anticipate, and then run the heck away. Don’t be That Person who decides to ‘investigate’. Never ends well.