Opinions: everyone’s got ‘em. This could not have been made more apparent after the recent result of the EU referendum in the UK. However, this is not intended to be a politically-charged post, nor a canvas for my own personal opinion. Because if recent events have made anything clear it’s that opinions are like the brains they’re made in: downright messy.

Divisive appears to be the most fitting word to describe the whole thing – and not just literally in terms of the outcome, which will now see the UK leave the EU. As the referendum campaigns unfolded, I couldn’t help being struck by how utterly chaotic and misleading the whole process seemed – even for politics. Political parties were split and unable to form their own cohesive standing points on the matter. In the aftermath of the result, I have watched people I know to be rational, intelligent humans, lose it in social media comment fights with people they don’t even know. So, in order to restore an ounce of normality to the world, I’ve decided to address this the only way I know best – talking about brains – and hope that normal service will resume soon…

So what has this got to do with the brain?

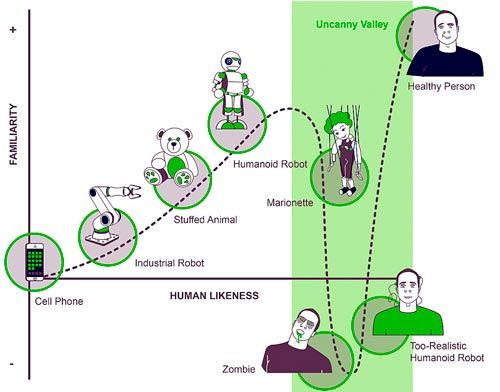

In a nutshell, the whole biological point of having a brain is that it allows you to receive information about all the stuff that’s going on around you, make some kind of sense out of it, and then translate this into appropriate actions and decisions which you then carry out. And, as brains go, humans do this pretty darn successfully: our domination of an entire planet being a case-in-point. But sometimes your brain is irrational in ways we’re blissfully unaware of as we bumble through life trying to make the right decisions in the face of quandaries such as: ‘how many consecutive episodes of New Girl is ‘too many’?’, ‘is this cheese really that far past edible?’, and ‘should our nation leave an international union it’s belonged to for decades?’ Consciously, you might be the most rational and open-minded of people but unconsciously, your brain is still capable of implicit bias on the sly without you noticing, especially in response to things other humans say and do.

‘No, I’M the most opinionated!’

We all know at least one person who will loudly proclaim that they ‘don’t care what other people think’ when it comes to their life decisions. And this may well be the case…as far as they’re aware. However, as social animals, the human brain has evolved so that actually we are very much influenced by what other people think of us – to the extent that patterns of brain activity seen following social rejection are incredibly similar to those associated with physical pain. Our desire to be accepted by social groups has both good and bad sides, but mostly makes for a lot of weird and baffling things happening when a bunch of like-minded brains get together. One well-documented example of this is group polarisation. If you stick a group of people together with the same opinion on something (for example: ‘you should always put the milk in first*‘), rather than conform to the average view of the group (‘tea’s quite nice if you put the milk in first’), individuals’ viewpoints will actually become more extreme (‘the milk should go in first, and anyone who disagrees should be slowly and painfully drowned in a scalding vat of their own incorrectly-made tea, the heathens!’)

#relatable

We identify most strongly with groups of people who are like us, and perceive those who are different, or outside the group, as a threat to its integrity. In keeping with this, there are lots of subtle ways that our brains can generate bias in our perceptions of people different to us. This might be people with different tea-drinking habits to you, or, more scarily, people of a different race to you. Implicit racial bias has been shown in several different types of study. For example, when a group of white American subjects were asked to pin-point when the expression in a gradually changing series of face images changed from ‘hostile’ to ‘happy’. It took them much longer to do this when the faces were black than when they were white, suggesting the possibility that anger was perceived in faces of a different race for a longer proportion of the ‘hostile-to-happy’ spectrum that subjects were shown. I’m sure you can see how this is not particularly great news.

Confidence: being flamboyantly wrong

We generally perceive people who are confident as being more convincing. This has been widely shown but particularly in studies mimicking witness testimonies in courtroom: witnesses who come across as confident when they speak are deemed to be more credible than those who appear hesitant. However, confidence does not always mean someone’s right (I know?!). In fact it’s been repeatedly shown that those who perform worse in a test or task tend to believe they’ve done better than they actually have: not only have they done badly, but they lack the ability to evaluate and recognise this. The reverse is seen in people who’ve done well in a task: they generally assume they’ve done worse than they have. This phenomenon is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. So there you have it, people who are wrong – they might be telling outright lies, or spouting incorrect statistics – can dazzle you with their confidence, all the while thinking that they’re doing a tip-top job of whatever it is they’re doing. A memory task in a lab. Trying to convince a nation how to vote in a referendum. Potayto-potahto.

I got the itch to write this post, not so much in reaction to the result of the referendum, but rather as some food for thought in reaction to the bewildering lack of rationality that, for me, seemed to characterise the whole event. I’ve had conversations with people voting both ways, and been amazed that in several cases they’ve been unable to explain to me in what I consider to be meaningful words, the evidence or even the thought processes which lead them to their decision. And so I hope this post serves to highlight something which I think, given recent political events (and future ones, what with the US Presidential Election coming up), we as humans would perhaps all do well to remember: your brain is biased and irrational. Sometimes without you even realising, and especially in the context of groups of people, and especially in the context of groups of people who are different to you. So when it comes to making decisions, no matter what your opinion on a matter is, we owe it to ourselves to first ask: ‘but why do I think that?’

Because opinions can be quite a rabbit hole, with your brain subtly and implicitly pulling the strings. Sometimes, it pays to look for this before you leap.

*I don’t drink tea. Calm down and go and put the kettle on for the mob you’ve just assembled. (Or, on second thoughts, might be safer if you don’t.)